Condition Reports

Before a conservation treatment can be started, a conservator must diagnose the condition of the painting and document their findings into a condition report. George Stout, author of The Care of Pictures, a helpful resource for the non-conservator, summarizes: [T]he picture is looked over for its general appearance, for the earmarks of material, the kind of support it has, the thickness of ground, the markings in the paint, the distribution, tone, and type of discoloration. It is studied microscopically over the surface, and then the reactions of the different layers are tested with a range of solvents….When all of this has been done, a plan for removal is devised, the materials and tools are brought together, and the work starts…Factors of timing, temperature, and manipulation are a part of it.1

The AIC Code of Ethics highlights the importance of documentation, stating “The conservation professional has an obligation to produce and maintain accurate, complete, and permanent records of examination, sampling, scientific investigation, and treatment. When appropriate, the records should be both written and pictorial.”2 Such documentation, they explain, helps “establish the condition of cultural property” which can help provide information for future conservation treatments, “increase[e] understanding of an object’s aesthetic, conceptual, and physical characteristics,” and provide records to avoid legal predicaments or misunderstandings.2 At minimum, this report should include the name of the artwork, the name of the “examiner,” the date of this examination, and the “structure, materials, condition, and pertinent history.”2 Creating a condition report both expands the communicable knowledge base on a particular painting and also covers the conservation practitioner from legal recourse in case the painting is mishandled or otherwise damaged after the artwork leaves their custody.

In The Art of the Conservator, Andrew Oddy also gives an overview of how a conservator would develop their condition report. Apart from diagnosing ageing or acute damage, a conservator must determine how much previous restoration work has been done to a work of art. The conservator looks for differences in color and texture by eye and through a microscope, and they can use gentle cotton swabbing with various solvents to determine if a “fake patina” varnish, a brownish-tinted glaze called a “scumble,” has been applied.3

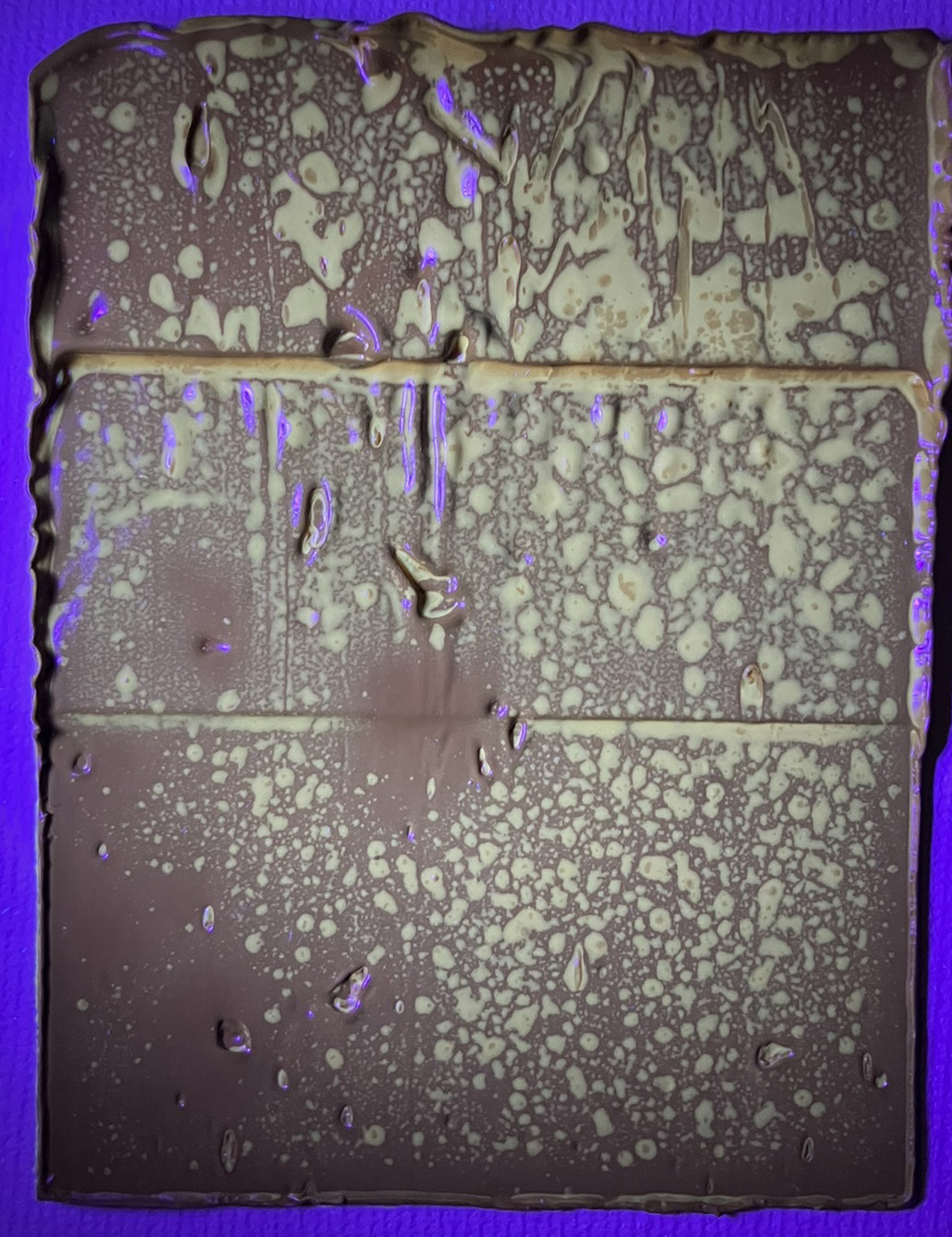

Different types of light can be used non-destructively to image paintings. UV lamps reveal bright fluorescence of some newer organic materials to highlight overpainting.3 X-ray radiography is a useful 2-D imaging technique, where certain materials will absorb a lot of the x-ray, whereas others will be more transparent to it, such that the x-ray passes through and leaves a mark on the film, so in many cases disparate materials can be distinguished.

Oddy writes that the “materials may have changed, and been supplemented by machines and scientific instruments, but in the end the four basic stages of conservation – stabilisation[sic] (arresting the progress of decay), cleaning, repair and restoration – have not changed since scientific conservation began over a century ago [as of 1992].”3

Sometimes a conservator may not recommend any treatments, only conditions for storage or display. “Passive” or “preventative” conservation (link) is when a work of art is stored in proper environmental conditions, whereas “active” conservation is when an intervention such as cleaning is taking place.3 While conservators recommend temperature, humidity, and lighting conditions to museums, Oddy notes that museums do not always in practice have ideal environmental conditions, as the humidity and/or temperature can be excessive based on climate or fluctuate greatly (such as with human visitors exhaling during the day, and then the space emptying overnight, or with seasons changing) causing cracking, mold growth, or salt migration. Additionally, light may be too intense or use bulbs with damaging UV frequencies that fade pigments, pollutants and bacteria can erode material, or physical handling that deposits finger oils or vandalism can cause additional damage.3

Decision making on the extent of cleaning or other treatments is often dependent on the picture owner’s goals of the treatment, whether preventative care, conservation, or restoration is their priority. The picture owner could be museum or a private collector. In an interview with me, conservators Beth Nunan and Katelyn Rovito of Flux Conservation, a private practice conservation company, specializing in the treatment of modern paintings, which frequently works with both museums and private collectors, answered the question, “Who decides if a work gets treatment?” by first noting that the value of the insurance policy on the work of art usually determines the extent of treatment.4 Similarly, Kelly O’Neill of ArtCare Conservation, a private practice company who also works with a variety of clients, said they worked with insurance companies often. Beth described that a work of art would be covered by fine art insurance or inland marine insurance, a type of policy that covers high value objects for transport, as paintings are often transported for treatment or loaned out to other museums.4

Conservators diagnose the degree of acute damage and determine the cost to restore, and Beth notes that the price of treatment recognizes her value as an experienced conservator. Conservators deal with whoever is paying for the treatment, whether it is the insurance company, collector, or museum, and they only occasionally talk to the artist, if they are living. I also asked Kelly if they turn down requests for conservation work, to which she responded that they don’t like to say “no,” that there is no hope or it is impossible to restore, but sometimes the cost of repair is higher than the monetary value of the art, and insurance will not cover it.3

Beyond considerations of cost, conservators must discuss with the art owner what level of intervention is appropriate based on the condition of the work, aesthetic goals for display, historical considerations, and perception of authenticity. A surface cleaning alone to remove dust and grime would be the least disruptive to the painting, but the owner may prefer to have darkened varnish or old inpainting removed to attempt to revive the original appearance of the artwork. Old inpainting or overpainting, which are usually done on top of varnishes, are surface coatings that can usually be removed without disrupting the original oil paint. Removal of these obscuring layers would reveal the actual condition of the original paint, which may be very damaged and require new application of adhesives or inpainting. This removal, however, may be unnecessary or only partially necessary if the previous restoration is still in relatively good condition.

Restoration decisions about such subjective criteria have created public controversies such as that of the Sistine Chapel in the 1980s-1990s (see “Why Conserve?” page for more information on this controversy) and the cleaning without retouching of the Jarves collection at Yale (see “Historical Practices”). In both of these examples, the cleaning away of grime and past restoration work resulted in drastically different appearances of these artworks that shocked the public. In the pursuit of authenticity, have the cleaning of patina or removal retouching negatively affected the formal characteristics of the painting (see “Why Conserve?”)? Questions like this result in discussions between conservators, curators, art historians, and collectors over the course of action to be taken.

The conservator alone, however, is equipped with the technical expertise and interdisciplinary knowledge required to make these decisions, according to Stephen Hackney, a conservation researcher. He characterizes the cleaning discourse as complex and niche, noting that “[t]o understand the subject in its entirety, many interpretive skills are required for a multidisciplinary approach.”6 Hackney believes that “art historians, museum directors, or artists, none of whom are likely to have the background knowledge to add significantly to the technical debate” have participated in the discourse surrounding the restoration projects, such as that of Sistine Chapel, based on aesthetic ideas rather than technical ones.6 At the same time, he bemoans this burden, the “role” that conservator is expected to take on, either as a good little solider who defers all decision-making to the curator, or as the sole arbiter expected to boast all of the expertise of several fields.6

References

1. Stout, George L. The Care of Pictures. New York: Columbia University Press, 1948. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1975.

2. Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice of the American Institute for Conservation. 1994. American Institution for Conservation. https://www.culturalheritage.org/conservation-at-work/uphold-professional-standards/code.

3. Oddy, Andrew, ed. 1992. The Art of the Conservator. Smithsonian Institution Press.

4. Nunan, Beth and Katelyn Rovito, “Interview with Flux Conservation: Beth Nunan and Katie Rovito,” By Anna Perkins. March 21, 2025.

5. O’Neill, Kelly. “Interview with Conservator Kelly O’Neil.” By Anna Perkins. March 14, 2025.

6. Hackney, Stephen. 2010. “The Art and Science of Cleaning Paintings.” In New Insights into the Cleaning of Paintings (Proceedings from the Cleaning 2010 International Conference, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia and Museum Conservation Institute), edited by Marion F. Mecklenburg, A. Elena Charola, and Robert J. Koestler. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.19492359.3.1.