Damage and Defects

Overview

There are a variety of ways that paintings can be damaged, each requiring an individualized approach to resolve. In The Care of Pictures, conservator, museum director, and “Monuments Man”1 George L. Stout writes, “As soon as a picture is finished, it starts to deteriorate. Those first few days or months are the only time in its whole history when its condition is perfect.”2 The aging of materials results in a picture that is constantly changing.

Similarly, conservator Andrew Oddy writes in The Art of the Conservator, “It is a commonly held fallacy that once an object enters a museum it is safe….Nothing could be further from the truth.”3 Oddy does not mean that works of art are especially unsafe in museums, but rather that museums are not always as controlled in terms of temperature, humidity, and light as recommended. He notes, too, that pollution, mold, or insects can cause damage to paintings.

When it comes to accidental damage, “carelessness” is the main culprit, according to Stout. Stout illustrates, “Paint gets scratched or marked…by drips of water, or splattered by scraps of food or stained by drink. Mold grows in it and insets speckle it….Flies have worked a particular plague on the early, unvarnished pictures of Europe. The excrement of these insects is brown and [acidic].”2 Handling can cause mechanical damage, and poor storage, especially in times of war, can cause the condition of a work of art to deteriorate. Stout describes, “Pictures can get scratched when they are carried about, dropped, or poorly packed.”2 Oddy also notes that works of art get damaged by deliberate vandalism.3

Stout, Oddy, Moss, and others describe the common defects of damaged paintings:

- Varnish accumulation of dust or grime

- Varnish darkening

- Bloom or clouding

- Varnish embrittlement and cracking

Paint Defects

- Fire and smoke damage

- Paint accumulation of dust or grime

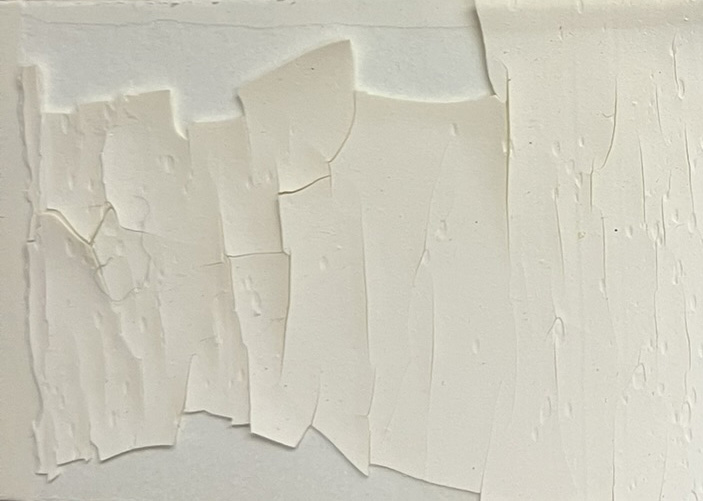

- Cracking

- Pigment discoloration

o Fading

o Darkening

o Chemical bleaching

o Chalking

- Mottling from old restoration work

- Loss of opacity (pentimento)

- Mold

- Oil discoloration

- Vandalism

- Overcleaning

Substrate & Ground

- Wood or animal glue swelling and shrinking with humidity changes

- Animal glue ground or lining as food for mold and bacteria

- Stains, discolorations, and scars

- Cracking

- Rodent and insect damage

- Water

- Tears and holes

- Wood cleavage

- Wood warping

Surface Defects

On the topic of damage to surface coatings (varnishes), Stout asserts: “[U]nless they have actually penetrated into the paint layer, they will have done no permanent damage, and they can be removed.”2 If this damage is only to the topcoat sealing in the actual pigmented paint, then cleaning or removing the varnish, or “surface treatment,” should reveal a painting in fairly good condition.

One main source of surface discoloration is the buildup of dirt on the surface, which is the least damaging defect, according to Stout.2 He writes, “Whatever settles on the wall around a picture naturally tends to settle on the picture also…A speck of dust may become a small focus for condensation of atmospheric moisture and certainly dampness improves the chances for a surface to hold any grime that may come its way.”2 Sometimes, dust and grime can be mechanically brushed away, and in other cases, some solvent may be required to clean the surface of this foreign material, and in still other cases, the varnish must be completely removed.2 A varnish is usually removed by using a solvent or solvent mixture to dissolve the resin, a solvent which the conservator has tested and determined to be effective without damaging the underlying paint.2

Another common source of surface discoloration is the coating itself oxidizing over time. Varnishes made from natural resins like copal or damar are especially known to yellow or brown, creating the “patina” effect but also obscuring the color details of the painting underneath. Stout describes, “[W]hen first put on, a varnish can be considered as a transparent film like glass. Before many years, however, clarity diminishes. The glass seems to be colored yellowish brown…and it begins to look rough, shot through with cracks.”2 These sorts of varnishes often look transparent and highly glossy over the first few years, hence their use by artists and past restorers, and historically were the only options for protecting the underlying paint. More modern varnishes, like those made from acrylic or PVAc binders, are much more chemically stable and resistant to yellowing than traditional varnishes and have become common.

Another result of these varnishes oxidizing is embrittlement or cracking, which may be large and apparent, or which may be microcracking, which reads as cloudy to the naked eye. Stout nicely explains, “Light cannot travel in straight lines….The difference between this and a fresh coating is the difference between ice and snow.”2

Paint Defects

Fire and Smoke Damage

Fortunately, Stout explains, surface coatings take most of the fire damage of small burns, protecting the underlying paint. When there is a large fire, “short of completely destroying a picture, [scorching and heavy smoke] can blemish [the painting] a great deal, for with a house fire there are extreme heat, fumes, and the action of steam when the fire itself is attacked by water.”2 He notes, too, that the acid from fire extinguishers can also be damaging to a picture. When a painting has been damaged by a fire, some loss of original material takes place, and the loss must be filled in.2 Stout characterizes fire as “probably the biggest risk of accidental damage to pictures.”2

Conservator Matthew Moss describes the effect of scorching on a painting: “The pigment may shrink into the form of pimples and coagulate into concentrated islands of burnt color. Fire causes the pigment layer to bubble and blister and the melting paint film to run and flow to the bottom of the support.”4 Such defects are almost impossible to restore to good condition, but if the damage is not too extensive with minimal blisters, according to Moss, a softening agent can be applied and the hot table used to press the paint film back together with the substrate.4

Alas, Moss notes that conservation laboratories are often at risk of fire due to their use of flammable solvents and electrical equipment, like hot tables used for smoothing down folds or flaking paint.4 Thus, conservators should make sure to properly store hazardous materials in flammability cabinets and maintain their electrical equipment, in addition to having a plan to quickly transport art out of the building in case of fire.

Dust and Grime

By contrast to fire, dust, according to Stout is “the smallest risk of damage.”2 He highlights the importance of storage conditions, such as keeping a painting under glass or in a box, to prevent the accumulation of dust.2 Dust can be brushed away if light or cleaned away with a gentle solvent if more stubborn.

Pigment Discoloration

Pigments can change color by fading, darkening, chemically bleaching, and chalking. Both fading and darkening are related to light exposure. Oddy describes how light affects pigments:

[W]hen an object is exposed to bright sunlight, some of the compounds which make up the object may absorb enough energy to cause the molecular structure to break up, and the color changes as a result. Light energy can also be absorbed by other compounds which can then react with oxygen, water, and other chemicals present in the air in small amounts.3Different frequencies of light have different effects on pigments. Stout clarifies that UV light is particularly damaging to pigments: “Direct sunlight is the strongest fading agent. Ordinary artificial light…or from lamps or candles is the weakest.”2 Museum glass or UV protective varnishes can greatly slow down the rate of pigment discoloration.

Whereas fading is most noticeable in dark colors, darkening is most noticeable in light colors. Stout highlights the reactivity of lead white when exposed to air (if underbound in the paint film) – lead white becomes very dark.2

Chemical bleaching and chalking are two other defects that affect pigment color. Both of these phenomena occur with the common pigment ultramarine blue. Stout notices that this pigment is weak to acid exposure and can decompose completely if an acid is mistakenly applied.2 The resulting fading is known as “chemical bleaching.”

Chalking is an effect caused by underbound pigment, where there is not enough binder to protect the pigment. This may happen if the paint is formulated with too little binder, or the binder degrades over time. The paint film loses gloss, and a matte, “chalky” surface remains. Sometimes this underbound effect was by design: since ultramarine blue (synthetic lapis lazuli) looks much brighter when underbound, this effect was put into practice in European paintings made before 1500.2 The artists mixed very little pigment with binder, usually egg or animal glue, to achieve a brilliant lapis lazuli or azurite.2

Light exposure can also cause chalking with certain pigments. The exposure of oil paint films made with ultramarine blue and some other inorganic pigments can result in both a loss of gloss and color fading. Chalking can be problematic if varnish is applied over top, as the pigment could potentially be removed if the varnish is later removed, a defect called “skinning.”2 Varnishing a chalked painting will also change the color, as the pigment is wetted out by the addition of a binder.2

Cracking

A hallmark of an oil painting is that it will inevitably crack over time. Whereas water-based acrylic paint dries by water evaporation, oil paint dries through chemical reactions. Because of this curing method, the initial touch-dry time of an oil paint, depending on the pigment and formula, can be days to weeks, much longer than an acrylic. Oxidation causes the oil (usually linseed) to cure and crosslink over time, hardening the paint film over the span of many years until it becomes brittle and may crack from stress or strain. Stout explains that “[t]here is no way to prevent this entirely in the mixture of the paint itself, for a film that has so little medium that it will not crack under any circumstances is a film too weak and porous to stand the normal conditions of exposure which pictures have to take.”2

There is no way to prevent cracking altogether, but visible or accelerated cracking can be mitigated by artist’s following rules like “fat over lean,” where slower-drying layers are applied over quick-drying layers, and not the other way around. “Fat over lean” means that solvent-rich layers are applied first, and subsequent layers have less and less solvent and more and more oil medium.

Raking light (light shining at an angle rather than facing a picture) can help a conservator see flaking or lifting paint. Moss writes that this light “throws defects, light impasto or repairs into relief.”4 The shadows cast by the lifting texture draw attention to the damage so that it can be repaired, which may require flattening or an adhesive.

Oil Discoloration

Another inevitable feature of oil paint is its yellowing or darkening with age. The oxidation reactions result in new chemical bonds that absorb light, resulting in the acquisition of a hue. The faster-drying an oil is, the more color it is likely to acquire. For instance, linseed oil has more reactive sites (double bonds) than safflower oil, and therefore linseed oil dries faster and is more durable and resistant to cracking than safflower oil. Safflower oil is much lower in color and less reactive than linseed oil, which is very desirable to the artist, especially with whites or blues, but its lower reactivity means it is not as good at forming a durable film that will resist cracking. Also, some of safflower oil’s fatty acids are non-drying and can weep out of the paint film after some years. Linseed oil, though it yellows more, is a more robust binder based on this variety of factors, which is why it is the most common oil paint binder.

UV-protective glass or varnishes can help slow down the yellowing of the oil paint, but other than preventative care, there is not much a conservator can do about the paint itself discoloring, since original work should not be removed. Sometimes darkening of the oil binder can be caused by dark storage conditions in a defect known as “dark yellowing,” and bringing the painting into indoor lighting conditions for a couple of weeks can reverse most of this darkening.

Old Restorations

With the passage of time, old restoration work may cease to match the original paint, creating a noticeable mottling effect. This happens because the materials used in retouching do not match the composition and/or age of the original paint, and the retouching may darken or otherwise change relative to the underlying paint.

Sometimes this contrast is only visible once a yellowed surface varnish is removed. Moss employs the example of Peter Paul Rubens’ Chapeau de Paille, where conservator Paul Coremans discovered that the artist had modified his own work:

Discolored old retouching needs to be removed to restore the unity of the painting. Fresh retouching may indeed be less extensive than the old retouching that is removed, as “often these mottled discolorations amount to ten times the area of loss” since older techniques commonly resulted in extensive overpainting.2

Pentimento

An odd defect that can happen to an oil painting is “pentimento,” which Stout describes as a “progressive change of refractive index in an oil painting” resulting in a more transparent paint film, where top-layer glazes that were once opaque now show the artist’s underpainting or underdrawing.2 While this defect does not reflect the artist’s intention, it allows the public to better see the painter’s method, so a conservator may leave pentimento after consulting with the owner of the painting.

Mold

Mold, a type of fungus common in the air, can wreak havoc on a painting. Light or dark spots will usually appear first on the back of a painting and eventually show through cracks in the oil paint on the front.2 Stout describes, “Mold feeds on the materials in the pictures that it infests, and some…is naturally destroyed. Paint gets pitted or otherwise marked. Ground and support are weakened. There may be a good deal of staining.”2

Mold only grows at high humidity, so a proper storage environment limits this risk. Stout specifies that mold “will not grow unless the relative humidity in a room exceeds 60 percent during a long period and usually 70 percent for a shorter period.”2 While some museums and geographic locations may not have issues maintaining a lower humidity, Stout cautions that “[t]here are not many houses where pictures are kept that can hold relative humidity below the 60 percent level throughout the year.”2

Animal glues used as grounds or adhesives can also provide food for mold and bacteria, encouraging them to grow.2

In the case of mold growth, Stout recommends moving the painting to a dry environment, brushing off the mold, and then fumigating the painting in a box with chemicals that can act as a fungicide, biocide, and insecticide, chemicals that kill fungi like mold, bacteria, and insects, respectively.2

Vandalism

Vandalism can be additive, where markings have been made on top of the painting, or destructive, such as cutting or tearing the canvas. Moss provides the example of Il Perugino’s Pietà, writing, “Cleaning revealed that vandals had lacerated most of the figures with swordstrokes.”4 Intentional damage can be some of the most difficult to repair since the materials used may not be readily removable, or weaving together tears in canvas can be very laborious.

Overcleaning

When a painting is old enough to have been restored multiple times, it may have endured harsh cleaning treatments to remove darkened or dirty varnishes, treatments that disrupted or removed the paint itself. Removal of original color changes the aesthetic qualities of the painting, changes which “were certainly not envisaged by the original painters,” according to Moss.4 He describes the use of caustic soda, lye, and pumice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, “result[ing] in the loss of glazes, half-tones and those final retouches applied by the painter which help give the painting its unity and appearance.”4

Pietà also suffered overcleaning damage. Moss writes, “The figure of the dead Christ which restorers had abraded by using caustic soda…was severely affected….Amateur picture cleaners tend to concentrate on the principle subject of the composition, which is why those areas are so often the most severely affected.”4

In such cases, conservators may decide not to remove old retouching, since there may not be much left of the original. According to Moss, “Whether to remove all accretions in a much-restored work of art is a difficult question. If you remove all later additions in order to reveal as much as possible of the original, what remains may be little more than a fragment.”4

Substrate & Ground

Distortions

Stout describes that the development of textures such as “[g]rooves and wrinkling, bulges, and other distortions of thin supports are easily seen at the face of a picture and may be disfiguring to the design.”2 That is to say, defects in the support and ground are often apparent to the viewer and must be repaired. They can often indicate that the support is under some sort of stress or strain, according to Stout, such as a canvas painting becoming misaligned from an unmitered stretcher. Sometimes a hot table can be used to smooth out texture, and other times, the substrate requires attention, such as relining the canvas.

Stains

Stout notes that stained fabric is not typically a problem for oil painting, since the paint is opaque enough to cover this discoloration.2 If the stain is caused by the natural color in the fabric, it is likely not a concern for the conservator, whereas staining from mold, insects, or rodents is a concern due to the detrimental composition of these foreign materials.

Rodents

Rodents like mice and rats can chew on the canvas, consuming and tearing material, and their excrement stains and poses a biohazard. Artist paint formulator and AIC speaker Ulysses Jackson has treated rodent-damaged acrylic paintings. To sanitize and remove the dark stains as best as possible, Ulysses recommends brushing away the excess biohazardous material and then steam vacuuming the back of the canvas with a mixture of diluted stabilized bleach (benzene sulfonamide, n-chloro-4-methyl, sodium salt) mixed with a cleaning surfactant (Ecosurf EH-6).5

Insects

Common insect pests include carpet beetles, moths, and cockroaches, which eat organic material like canvas and wood. Flies are particularly problematic, according to conservator Barbara Appelbaum in Guide to Environmental Protection of Collections, since their excrement is “highly acidic” and “erode[s] small pits in the paint surface and leave[s] brown circles of discoloration.”6 Cleanliness, maintaining a low relative humidity, and regularly inspecting the museum or storage space can help prevent an infestation.6

Swelling and Shrinking

Humidity changes cause wood panels and animal glues, like the rabbit skin glue commonly used as a ground over canvas, to expand and contract, and this motion can cause wood warping and/or cracking and cracking of the oil paint applied to the shifting animal glue.2 Because of the brittleness of aged oil paint films, they cannot stretch when the substrate expands and contracts, resulting in cleavage.

Past conservation treatments have worsened this problem. Many paintings were re-lined in their restoration history, meaning “to attach another fabric at the back of the original one with an adhesive.”2 Before 1900, Stout explains that it was common to use an animal glue adhesive concoction to reline a painting, which has caused damage to paintings, as this glue swells and shrinks with humidity changes, “loosen[ing] the paint” and causing cracking or paint loss.2 Because glue grounds and linings on canvas are so common, Stout laments that their use “is probably the greatest single cause of damage to pictures.”2

Of flaws in the support, Stout writes, “The flaw to look for is the kind that may get worse….[In the case of wood] Even a small check is a sign that something has gone wrong. The wood can not adjust itself to some strain in its structure or strain caused by an attachment to it….That can go on and cause more damage.”2

Tears and Holes

Tears and holes in canvas paintings can be caused by poor handling, vandalism, fire, or rodent damage in addition to the embrittlement of the canvas, ground, and oil paint itself.

Conservator Katelyn Rovito of Flux Art Conservation, a private practice conservation company, describes why simply gluing a patch to the back of the tear does not work: “Stress travels across the canvas and transfers to the unstretched patch. The patch, adhered only to the fibers at the back, will push forward and create a bulge noticeable on the front of the painting.”7 For this reason, historical restorers would reline the whole canvas, but this has fallen out of favor due to contemporary conservator’s preference for minimal intervention. Rovito explains, “Lining does evenly distribute the stress, and although this treatment works, it is also invasive and irreversible. Today, paintings conservators tend to favor local treatments and only line a painting as a last resort.”7

The ideal remedy for repairing tears is to weave fibers matching the canvas thread by thread so that the result is as (literally) seamless as possible.7 Such meticulous work is done with tweezers and a crochet hook, looking through a microscope and employing water-resoluble glue to adhere the threads together.7 To reinforce the mended tear, an archival tissue can be adhered to the back with a water-blocking, reversible adhesive to inhibit damage to the water-soluble adhesive that was used to reattached the threads.7

In the case of a hole, where there is a loss of material that must be filled in, rather than just sewn together, a scrap of canvas of a matching weave is cut to the shape of the hole, and then the hole is patched with some adhesive and tissue to fill in the loss and reinforce the repair.8

Wood Cleavage

When more than one piece of wood is joined together to make a panel painting, and they are coming apart from each other, or if a solid piece of wood has split, the two pieces can be stuck together with an adhesive such as a synthetic acrylic, according to Moss.4 In the past, joints, called “battens,” would be added to the back, but now, Moss describes that common practice is to chisel out the cracks on the back and inlay wood veneer into the grooves with some glue, leaving some space between the inlay and the substrate to give the wood room to expand and contract without causing more damage to the fissure.4

Wood Warping

As wood dries out and ages over time, a panel that was originally flat can become curved. Moss describes how to resolve this defect: “Warping or curving of the original timber support is sometimes overcome by introducing extra timber onto the rear of the panel,” which also involve chiseling and inlaying veneer on the back.4

References

1. Ueno, Rihoko. 2012. “Monuments Men in Japan: Discoveries in the George Leslie Stout Papers.” Smithsonian: Archives of American Art Blog. https://web.archive.org/web/20121109045148/http://blog.aaa.si.edu/2012/10/monuments-men-in-japan-discoveries-in-the-george-leslie-stout-papers.html.

“Stout was a member of the Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives Section (MFAA) of the U.S. Army—known colloquially as the “Monuments Men.” This group was charged with the protection and damage documentation of cultural monuments along with the investigation, location, recovery, and repatriation of art that had been plundered systematically by the Nazis. Stout was a prominent art conservator working at Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum and one of the first to be recruited to the MFAA Section. As a Monuments Man, Stout accomplished a great deal: he supervised the inventory and removal of several thousand art works from repositories hidden in salt mines, churches, and other locations.”

.

2. Stout, George L. The Care of Pictures. New York: Columbia University Press, 1948. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1975.

3. Oddy, Andrew, ed. 1992. The Art of the Conservator. Smithsonian Institution Press.

4. Moss, Matthew. 1994. Caring for Old Master Paintings: Their Preservation and Conservation. Irish Academic Press.

5. Personal communication with Ulysses Jackson, Dec. 15, 2025.

6. Appelbaum, Barbara. 1991. Guide to Environmental Protection of Collections. Sound View Press.

7. Rovito, Katelyn. n.d. “Tear Mending.” Flux Art Conservation. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://www.fluxartcon.com/influx/0vh0z3uesmkhqxr281ihc4her3wnry.

8. The Museum of Modern Art, dir. 2019. Microscopically Reweaving a 1907 Painting | CONSERVATION STORIES. 8:18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odeG3HBEpSQ.